The origins of world trade can be traced back to the 1st century BC, when luxury products from China, such as spices and silks, started to appear on the other side of the world in Rome. It was then that commerce stopped being an exclusively local activity, but it wasn’t until the 19th and 20th centuries that globalization accelerated and started to define everything from the way we work and travel to the way we foster relationships and communicate.

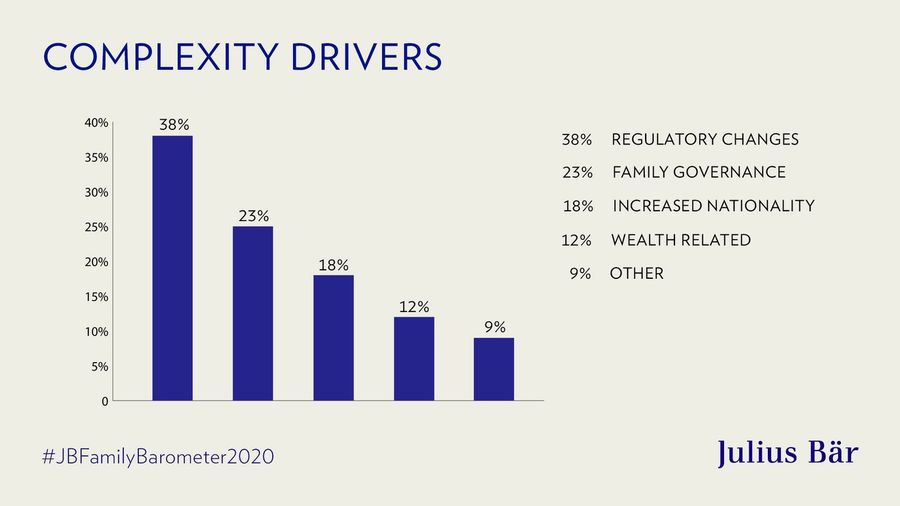

Globalization has created boundless optionality, but for families, the advantages have also been accompanied by a slew of complexities and challenges. In the Julius Baer Family Barometer 2020, 90 percent of relationship managers surveyed agree or strongly agree, from their experience with wealthy clients, that life has become more complex to manage as a family over the past decade. Some 80 percent state that the number of family advisors has grown and now covers aspects that were not covered 10 years ago. Regulatory changes were cited as the most prominent hurdle, but family governance was a popular answer too – a concept that is perhaps as difficult to define as it is for many families to address.

According to the UK’s Chartered Governance Institute, a membership body for governance professionals, the term refers to the way in which entities are run and to what purpose. It determines who has power to make decisions, and who is accountable. Governance should ensure that decision-making processes and controls are in place so that the interests of all stakeholders are balanced and respected.

But when it comes to families, good governance may become particularly tricky to safeguard on account of any number of things: members dispersing geographically, succession plans blurring, or motivations diverging. Of those surveyed, 88 percent said they believe the next generation will have a wider range of issues to deal with than families today, underscoring an urgent need for families to consider solutions – ideally well before the gravest problems materialize.

Though some form of globalization has been in motion for centuries, international migration has increased dramatically within just the past few decades. Research conducted by the Washington DC-based Pew Research Center showed that in 2017, around 44 million US residents were living outside their birth country – around five times as many as in 1960.

If classed as a national population, the global migrant population would now rank as the fifth largest country in the world, and, although many migrants relocate because of war, poverty, or civil unrest, Pew found that the majority are driven by opportunity: they’re not moving away from something, but towards something that might provide a more lucrative, interesting, or rewarding life.

Migration can stoke economic growth, encourage innovation, and lead to personal wealth, but for families, it inevitably leads to complications.

Scattered families

While entities like the World Trade Organization and International Monetary Fund have become prominent and powerful bodies in managing and controlling international trade and capital flows, the problems faced by families spanning the globe have often fallen between the cracks of policy and regulation. More fundamentally, the scattering of individual families around the world can quickly lead to a misalignment of priorities and values. Different branches might develop their own ideals and traditions, leading to a breakdown in communication or even relationships, which in turn could complicate managing affairs – financial or otherwise.

As well as being increasingly international, families are becoming more multigenerational as life expectancy in many countries rises and family models change.

Though every family is unique, understanding the nature of the problems presented by globalization is perhaps the most effective way of combating them. The value of maintaining strong connections should never be understated, regardless of how large, diverse, or widely distributed a family is. A thorough and timely understanding of rules and regulations in different jurisdictions, and how they may affect family and business affairs, is crucial.

As well as being increasingly international, families are becoming more multigenerational as life expectancy in many countries rises and family models change. It’s paramount that people appreciate the implications of this. Life expectancy at birth in the European Union was estimated by Eurostat to be 80.9 years in 2017, compared to just 69 in 1960. Different generations will have different ways of interacting, upholding traditions or introducing new customs. This impacts how families function – and how they do business.

Birth rates around the world may be falling, but that doesn’t mean families will necessarily become simpler. Marriage rates in the EU are declining and divorce rates rising, but such commitments no longer define the parameters of the family unit. Legally recognized alternatives to marriage, such as partnership, have become more prevalent, while legislation in various countries has adapted to confer more rights on unmarried couples.

All these trends will contribute to the evolution and development of the global family in the years to come. Consolidating those preferences and values – often across different continents and time zones – relies heavily on strong communication, tolerance, and empathy. Globalization continues to put that to the test.

The coronavirus challenge

Just as steady demographic and societal trends have challenged global families, so too have entirely unexpected events, perhaps none so much as 2020’s coronavirus outbreak. As countries around the world were forced into lockdown, families had to come to terms with not only a new, socially distanced reality, but also mass cancellations of global transit, dramatically curtailed international trade, and a halt to other commercial activities.

Covid-19 is unlikely to have slackened the pace of globalization in the long run.

Navigating a sudden health crisis presented a litmus test for international families, some of which were forced apart by travel bans, while others were contained in the same location – perhaps for the first time in years.

Like international governments and businesses, families were compelled to experiment. In the face of not being able to move around freely, many became more comfortable relying on technology to communicate and do business. Some might have used the crisis to reflect on and reassess their ambitions, commitments, and goals. For others, the economic fallout resulting from the health crisis may have called for a fresh approach to addressing financial issues within the family unit, or thinking harder about succession planning.

Although Covid-19 has cast a fresh light on the interconnected nature of our world, it’s unlikely to have slackened the pace of globalization in the long run. The forces of internationalization are intact – if anything, the process may have become more complicated. Families will have to continue to adjust to them, from the political to the cultural, and the social to the economic.

As we move through the next decade, and as we adapt to a new reality, the issues faced by global families are unlikely to become less complex – from logistics to staying truly connected and dealing with decision-making around wealth and business. By being aware of past impediments, however, and by understanding the existing hurdles, it’s possible to anticipate what might be heading our way.

Globalization will always create both opportunities and setbacks. For a family, the art lies in being able to overcome the latter swiftly, while reaping the benefits of the former for years to come. It’s certainly not easy, but family life – as many of us will concur – rarely is.

Pohtography: Shutterstock, Julius Baer