It is quarter to four in the morning, February 21st, 2019. At Cape Canaveral in Florida, a missile carrying a small spacecraft called “Beresheet”, all blue and white, stands ready to launch. The famous countdown begins, thousands of viewers in Israel and many more worldwide are witnesses to the historical moment that would put Israel on the world technological stage. Among the spectators that came to the Israel Aerospace Industries control center, sits Morris Kahn, the man without whom none of this could have happened.

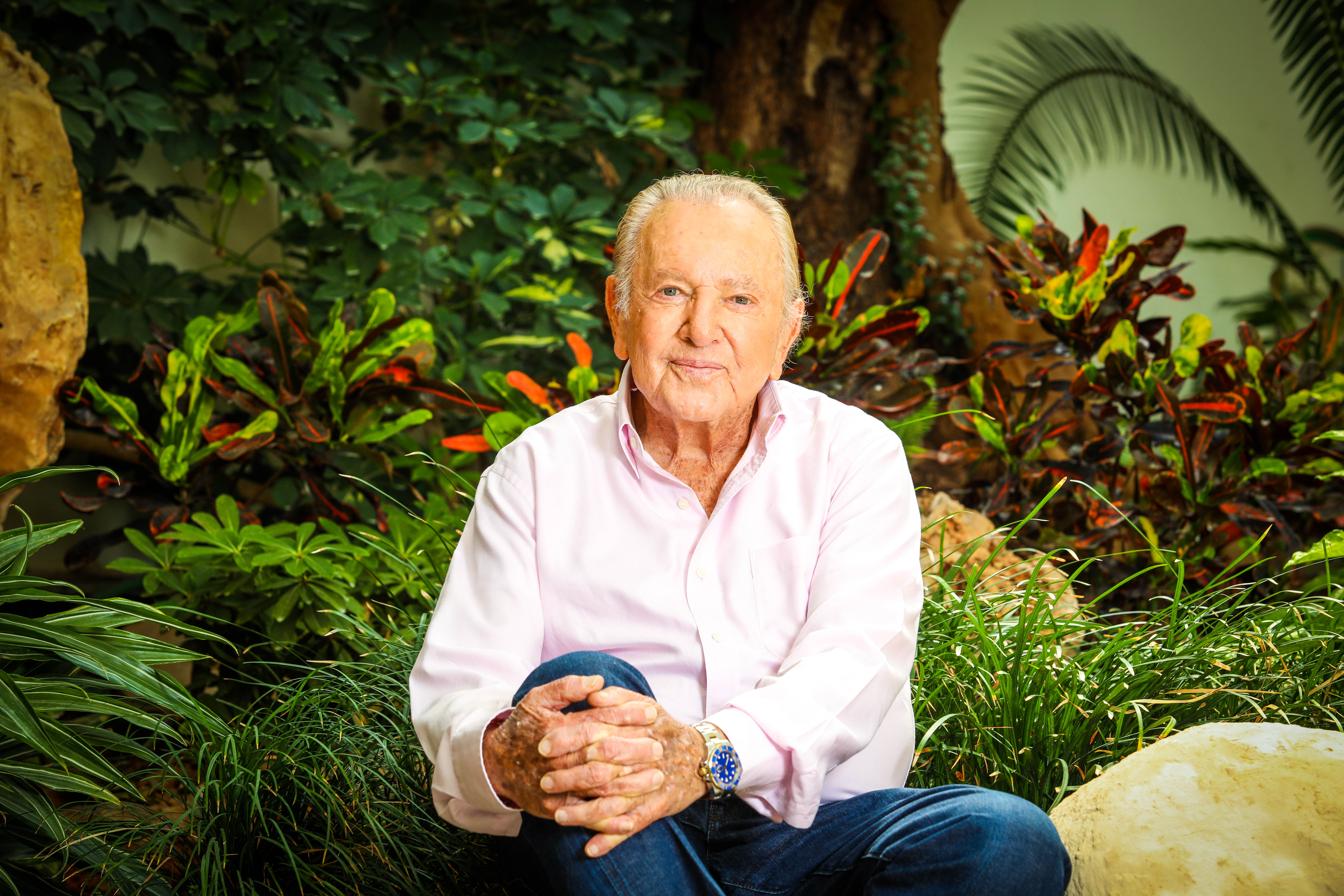

Kahn, age 89, was born in South Africa in 1930 to a poor Jewish family, who immigrated to Johannesburg from Lithuania. He found the courage required for entrepreneurship when he was in school, as he began to produce and sell radio devices that operate on crystal (a radio that operates without a battery or electricity). After that he opened a bicycle ship and then moved into the jewelry business.

Apart from his business sense, Kahn was also endowed with a well-developed sense of justice. That same sense urged him to leave South Africa at age 26 and move to Israel along with his spouse Jacqueline (with whom he has lived for 54 years) and their two small children. “I couldn’t stand the oppression of the blacks at the hands of the whites. It disturbed me,” he tells. “So I didn’t want my children growing up in a country with no future either, which is why I wanted to take part in the building of our country.”

Kahn is indeed a full participant in building the country. In fact, since he immigrated in 1956 (after several failed business attempts), he managed to influence a number of fields in the Israeli economy. At the end of the 1960s he brought the Yellow Pages to Israel. In the 80s he founded the software company Aurec Information, which in time became Amdocs, and invested in a series of companies, such as Golden Lines, Netvision, and AIG. Kahn also initiated the observatory under the sea in Eilat, through the company Coral World, that he founded in the 1970s in addition to the aforementioned series of projects such as the “Beresheet” spacecraft, which is about to make a historical mission into space, on its way to making Israel the fourth country to ever get to the moon after the USA, Russia and China.

“Just start”

If you happened to get the chance to visit Kahn’s office in Ramat Gan, you could easily get confused and think that you had arrived to an ancient European hotel with classical design and rare furniture. But then, as you walk the hall to his office, it would be impossible to ignore the presence of Kahn – the halls are full of memorabilia that he has received over his years of traveling the world and his various occupations. Two motifs in particular stand out: water and space. Starting with the model of the spaceship standing at the entrance to the office building and greeting the comers and goers, progressing through models of Kahn’s various yachts displayed in the hallways, and arriving to the climactic enormous aquarium built into the wall of his office.

“I always found the experience of being underwater to be very spiritual,” says Kahn who still goes sailing and diving – two of his main hobbies which, characteristically, he does not keep to himself. “During one of my diving holidays, I got an inner ear injury and was unable to dive – so I was on the beach and met other people who weren’t diving. I thought about the fact that they weren’t seeing the corals and fish that I love so much, and then the idea came to me to build an underwater observatory, that would enable people to see the fish and the amazing undersea world.” That was how the Underwater Observatory in Eilat was born.

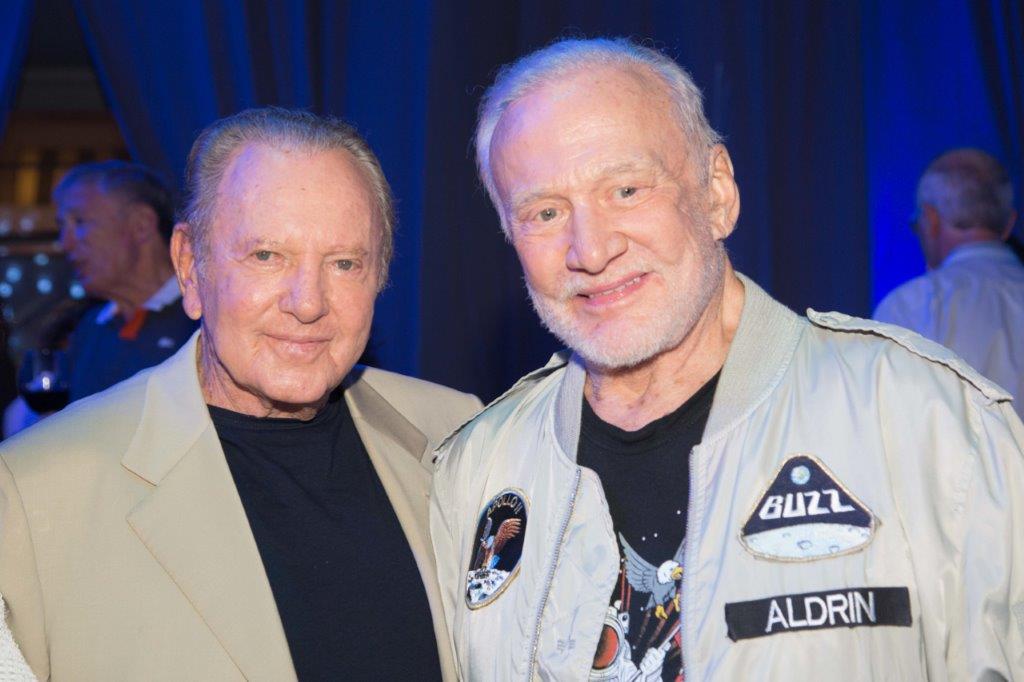

After the impressive aquarium, the next thing to catch your eye in Kahn’s office is the photo of him standing beside his good friend, the astronaut Buzz Aldrin, the second man to walk on the moon, immediately after his fellow Apollo 11 crew member, Neil Armstrong.

Aldrin and Kahn are partners in an organization called Sea Space Symposium, an organization that includes many members of NASA and other space agencies that have been to space and walked on the moon. “These are people that are involved in the ocean and space,” says Kahn. “Buzz and I have been friends for the past 15 years, we are the same age and we are going to go diving together.”

Aldrin and the symposium are also responsible for bringing Kahn into the world of space. And one could say that they have a good deal of “shares” in the success of “Beresheet” and the group responsible for it, SpaceIL.

Kahn met the founders of SpaceIL by chance. “I went to a lecture at Tel Aviv University, and three young students were up on stage, saying that they are going to participate in a Google competition with the aim of landing a spacecraft on the moon. So I went up to them and asked them if they have a source of funds. They said no. Afterward I asked them how they thought they would do it? And they said that they hadn’t thought about it yet. Ultimately I gave them $100 thousand, no questions asked, and I said: ‘just start’”.

Sleepless Nights

Until that point I didn’t know what $100 thousand looked like,” says Yehonatan Weintraub, one of the three founders of SpaceIL (along with Yariv Bash and Kfir Dameri) and a Forbes Israel 30Under30 alum in 2017. “Our original plan was a spacecraft the size of a cola bottle, but at some point we did a simulation and decided to enlarge the spacecraft, so the project wound up taking longer.”

According to Weintraub, Kahn was there all along. “After the 100 thousand he put in another $400 thousand and then another amount, and it progressed. When we had to make improvements, and it was clear that we needed more funding – he was there for us.” In the end, Kahn’s contribution added up to $40 million out of a total $100 million invested in the project, that lasted eight years until the launch.

“I didn’t think it would reach $40 million,” says Kahn. “At a certain stage, I started to try to raise funds. I got a significant amount from the Adelson Family and I had a few friends, like Steve Grand, Sammy Segal, Sylvan Adams, and the Schusterman Family – all of them gave significant contributions.”

According to Kahn, his billionaire friends, who he recruited for the benefit of the task, didn’t fully understand the space topic, but they wanted to help him finish what he had started. “It’s much harder to raise money to send a spacecraft to the moon than to give to the poor,” he says.

“This situation, that I took a lot of money in order to finish the project and we were facing difficulties, really worried me, to the point that I was unable to sleep at night,” Kahn reveals. “And then one night I reached a decision that no matter what, I will put in as much money as it takes to make this project happen and to live up to the commitments that I made to my friends. From that moment on I felt relaxed, though I cannot say the same about my bank manager.”

The Adelson family, for instance, wanted to contribute in exchange for writing “Am yisrael chai’ on the spacecraft, reveals Dafna Jackson, CEO of the Kahn Foundation, who was, among other things, responsible for the project’s fundraising. That is the story behind the writing that the whole country saw in the famous spacecraft selfie. “In general, most of the donors volunteered for this project from a zionist place – that is, in order to put Israel, this tiny country, on the moon.”

But for Kahn, lover of space and adventures, this wasn’t just a zionist project. The more time passed and his investment grew, so too did his involvement increase in the details of the project. “The financial aspect was just a small part of what I did,” he clarifies. “I was involved in every aspect of this project, not the engineering, because I’m not an engineer, but the rest of it. We had a lot of problems and I was there for all of them – without me this project would not end,” says Kahn.

“Beresheet Effect”

One of the things that connected Kahn and the three founders to the spacecraft project and was responsible for their uncompromising commitment to it was the added value that accompanies it. “What really helped us over the years was the children,” Weintraub explains. “From the beginning, we started as an organization that advocates education. We didn’t just work as engineers, we also made sure to meet with children and explain the work to them. And after a hard day of work, when you come to speak with a child, it’s energizing.”

For Kahn, the added value is more complex and he divides it into three parts. The first is a matter of national pride that a blue and white spacecraft will land on the moon.

The second is related to the significant help that he claims they received from the IAI, and his desire to get a spacecraft made by IAI into space. By the way, Kahn says that the IAI already signed an agreement with a German company to develop a joint space project of a similar scale. “We are seeing the fruits of the seeds we planted. I thought that it will take a long time, but this is happening fast,” he says.

The third and central piece is what Kahn calls the “Beresheet Effect”. The goal was to create a generation of people, who will be full of inspiration and will want to work in the space field – just like the “Apollo Effect’ that the Apollo 11 had. “I am moved when I see children in space costumes.”

Kahn and Jackson emphasize that one of the most important things that they want to convey through this project is the message to follow your dreams. To dare, to try, and not to give up. “When I explain my life to people, I always come back to this – don’t be afraid to fail. I failed many times and after every failure I shook myself off, got back up, and tried something else. I never thought of quitting trying,” tells Kahn, And speaking of failure, the obvious question is how will he feel if the spacecraft doesn’t wind up landing on the moon? “It’s possible that will happen and I will feel some disappointment, but in any case, the feeling of satisfaction with what we did – we tried, we sent the spacecraft into space, we controlled it, it operated as we planned. I am satisfied and very happy with what we have achieved thus far. And if we manage to land on the moon, that will be a bonus, but I won’t be terribly sad if we don’t.”

A present to himself

Kahn is a permanent member of Israel’s wealthiest people list since 1998, when he cashed in his holdings of Amdocs when it was issued in the United States and received $1 billion. Six years later, he added another 500 million NIS to his fortune, when he sold his holdings in the Yellow Pages. Although if you ask him, he stopped counting his money a long time ago. “I once met Arieh Filtz, one of the big building entrepreneurs responsible for Dizengoff Center and the like. He told me, ‘if you know how much you have, you aren’t rich.’” This rich man, according to Forbes’ estimate, has about 3.7 billion shekels, in 42nd place on Israel’s most wealthy list.

Despite his great wealth, two words that Kahn repeated the most during the interview were “happiness” and “satisfaction”, and you could say that those also best describe the man behind the billions. “I don’t feel rich,” he claims. “They say that the fact that I was born poor must make me appreciate wealth more than those who were born rich.”

Kahn tells that the most meaningful moment in his life was when he found his wife, who made his life happy. Despite this, according to him, money doesn’t make a person happy. “Money gives you the possibility to do things that you otherwise wouldn’t do. Money isn’t happiness, it is a tool.”

The tool that Kahn is talking about is not just meant to be used for oneself. With the help of the fortune that he amassed he can also contribute, and he has been doing so for decades, and to over 150 philanthropic projects at once: from environmental organizations, through financial assistance to the disadvantaged, projects in medicine and technology and projects such as Lead, which he founded 17 years ago that gives tools to the next generation of leaders and innovators in Israel.

“With the help of very little money you can change someone’s life. That gives me satisfaction,” says Kahn. “I want to see this generation of innovators, who make amazing things in Israel and make a huge amount of money, use some of that money towards the good of society. These are people with abilities, they can do big things and find such great satisfaction – it makes me happy. I’m not saying that they aren’t doing this – there are those who do and those who don’t – for them too, because the satisfaction of contributing is an indescribable feeling.”

One of the philanthropic activities that Kahn is most proud of (and for which he was also given a UN award) began 9 years ago, when he decided to buy himself a gift for his 80th birthday. The present was a philanthropic journey with a team of volunteers and eye doctors to a small village in Ethiopia, where there are many children living with congenital blindness, which can be fixed with a 25-minute operation.

“Not doing something like this is a crime,” says Kahn, who has kept up this activity until today. In Ethiopia, Kahn and his team sleep in tents, in tough conditions, with mosquitos and no air conditioning. During those visits they travel for hours from place to place – but according to him, he is his happiest there.

“We got to Jinka, a village in the middle of nowhere, and each time we gathered 600 children and saved their lives and, by association, that of their relatives. To this day we have operated on over 5,000 children. I can’t describe the feeling of pleasure that it gives me.”

Now that he is 90 years old, Kahn says that he does not think about age. “But it is important I make sure that as long as I’m here, I enjoy my life and keep up doing what I am doing – the truth is that I am making my dreams come true.”

Translated by Zoe Jordan