On September 2nd, the movie “Incredibles 2” broke the $600 million mark in North America. It became the ninth movie in history to do so, and the fourth to make it within eight months. It was preceded by “Star Wars: The Last Jedi”, “Black Panther” and “Avengers: Infinity War”. Outside of North America, we are seeing inflation in revenues – 2018 was the fourth year in a row in which at least four films reached billion dollars in global ticket sales, a club which until recently was highly exclusive – but now seems to be expanding at a dazzling pace.

This huge film industry was already declared dead, with the rise of television, and then again, with the home theatre system, and finally – with the internet illegal downloads of the 2000s. But Hollywood is still alive and kicking and skyrocketing to new heights: in 2017, about $40 billion worth of movie tickets were sold, of which about $11 billion was from within North America.

The necessity of increasing revenues can be better understood if you consider the fact that movie budgets have gone up greatly – resulting from the increasing investment in digital effects, global marketing campaigns, and huge salaries for the stars who demanded to benefit from this spectacle. These expenditures have to be covered. If at the end of the 1980s, the big movies, such as “Indiana Jones” or “Batman” were produced for about $60-70 million (around $120-140 million in today’s dollar) today, $200-250 million for a big movie is considered a standard budget. We have already seen movies spend as much as $300-400 million or more, like in the case of “Avatar” and the later installments of “Pirates of the Caribbean”, “The Avengers” and “Star Wars”.

The competition between the big films for the American viewer’s ticket price is more difficult than ever; despite the nominal growth in revenues, in the last thirty years, the average number of North American film-goers has been cut in half (7.7 tickets for every 1000 people in 1987, compared to 3.8 tickets in 2017). In 2017, the number of tickets sold in North America was the lowest it has been in 25 years. The giant classic theaters, which were an inseparable part of the cinematic and cultural scene for half a century, could no longer survive the new era – most have closed and those that remain now offer a greater number of screens rather than one big one.

A fateful week

How do studios manage to return these huge investments in this new era of increasing competition? The answer is improving the viewing experience, which makes it possible to charge more for your ticket, creating more aggressive marketing campaigns, but also by appealing to new audiences, namely, China.

Like movie budgets, average ticket prices have also risen faster than inflation in the last 30 years, thanks, among other things, to the rise in popularity of projection methods such as 3D and IMAX, for which a higher ticket price can be charged. As such, big theaters have been replaced with the “multiplex” such as Cinema City or Globus Max, which offers dozens of screens, while switching to digital screening, which increases the flexibility of the theater, allowing them to meet a large demand for a particular film.

There is a battle being waged over the number of tickets sold as well. The solution that the studios have found has been to turn every average-plus film into an event and to hold a large global launch. As a result, if in the past a good movie could be shown for six months to a year and accumulate revenues gradually, these days the most successful movies typically make a third of their revenues by the end of opening weekend, and two-thirds of their revenue in the first ten days. So the fate of the production, which lasts years and costs hundreds of millions of dollars, is determined within days and even sometimes within hours.

If we go back and compare how things look in the 80s and now – the peak revenue at the end of the first weekend of screening at the box office in North America has jumped tenfold since – from $25 million dollars for “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom” to the $257 million dollars that “Avengers: Infinity War” made by the end of its first weekend, earlier this year. No less important – this phenomenon, of opening with full force, has, in the last two to three years, going from an American event to a global event, and revenues from the rest of the world are likewise made mostly in the first days.

A strong global opening weekend is made possible by huge investments in marketing, which often amount to almost half of the entire production budget. This budget tries to create a buzz and make every movie into an event that must be seen – and fast. These days, great trailers alone are no longer enough. Before the big movies come out, we witness the creation of an entire world of content – comic books, viral campaigns on social media, and of course – merchandise and computer games, two fields that might yield several hundred million dollars to the rights holders.

The biggest success story is the Marvel superhero series which brought us the Avengers and all of the related films such as “Iron Man” and “Captain America”. After a series of mediocre attempts to bring some of the characters of the 90s and early 2000s comics to life, it was decided to produce a series of films on those characters that exist in the same cinematic reality, and who might sometimes make crossover visits to the other films. The beginning was the first Iron Man in 2008. Let’s have a look at the numbers then and now: 20 movies in the world of the Avengers have been produced at the cost of about $4 billion, and have brought in $17.5 billion in revenue to date. The revenues from related merchandise constitute many more billions, and another 12 movies are in various stages of production, along with several television programs.

Star Wars has also had a revival in the new era – in 2012, Disney (which also owns Marvel) acquired Lucas Film for $4 billion. This acquisition granted them all of the rights to the worlds of Star Wars and Indiana Jones, two of the most successful series in film history. Since then, Disney has released four films in the Star Wars world, which together earned $5 billion at the box office and pumped fresh blood into the endless world of merchandising Jedi knights. Next year will bring us the 9th installment, which will conclude the sequel trilogy, but Disney is already working on two additional trilogies and a television series, all of which will take place in a galaxy far, far away.

A matter of taste

With all due respect to the aggressive advertising in the existing market, the real potential for growth is Hollywood’s entrance into a huge new market – the enormous Chinese viewership. In 2012, China agreed, for its own reasons, to open the market for some of the months of the year to foreign movies – 34 foreign films are allowed to be shown per year, and the studios only receive a quarter of the revenue. At a time when Western movie theaters are closing, they are expanding in China.

Everyone wants a cut of this huge market, especially the locals who flock to American films. But movie taste is not the same, and some of the movies that were successful in the US failed in China, or the reverse. But there is a discernible trend of strong openings in the first weekend and rapid decline. In many cases, American movies are logging bigger revenues from their release in China than in North America. And it really is an enormous market – last year ticket sales for American movies in China reached nearly $3 billion (a third of total ticket sales). At this rate, within two years China will replace North America as the largest market for ticket sales in the world.

When so much money depends on it, Hollywood is willing to make a few concessions and adaptations to please its new audience and entice them to come out to the movies in full force. And so we get special content for the Chinese alongside local casting for smaller roles. “Iron Man 3”, for instance, was released in China in a different version than the rest of the world saw and included a number of scenes intended especially for the Chinese audience.

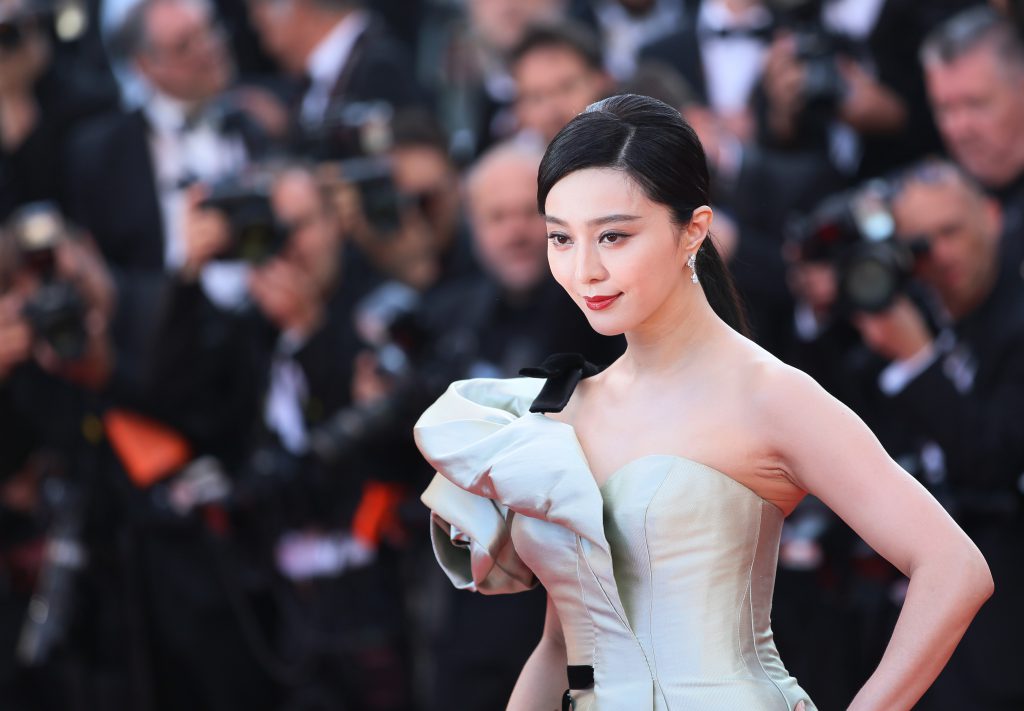

Meanwhile, Asian stars, whom most of the Western audience will not have likely heard of, are being cast in small roles in American films to add market appeal for the Chinese audience – Fan Bingbing, the biggest star in the industry who, according to Forbes ranked fifth in the list of the world’s most profitable actresses per film (and two months ago disappeared from the face of the earth, until it became clear that she had been arrested for tax evasion), appeared in a small role in “X-Men: Days of Future Past”. She herself admitted that her performance was aimed at attracting the Chinese viewership but added, half-jokingly, half-serious, that “ten years from now I will be the heroine of the X-men movie.”

This statement may well come true. Hollywood is going out of its way to please its new public. Try to remember the last time you encountered an evil Chinese character in a Hollywood hit. Movies like “The Departed” by Martin Scorsese, won the Oscar for best picture in 2006 and a film adaptation from Hong Kong was not screened in China after Scorsese refused to cut problematic scenes that challenged Chinese censorship. Two years later, Christopher Nolan’s “Dark Knight” was not even submitted for Chinese approval because of the presence of a dubious Chinese businessman character in the film.

But since then Hollywood has gotten the idea (money talks) and the Chinese villain characters have almost completely disappeared, and in their place are characters that present the Chinese in a more positive light.

Hollywood’s big stars also recognize the trend and many of them are looking for ways to integrate into the new market. It is not a one-way street: while Asian talents come to act in Hollywood, American stars and professionals have been doing the reverse: Michael Douglas appears in the Chinese “Animal World” this year, Bruce Willis and Adrian Brody act in “Unbreakable Spirit” about the Japanese bombing of China during World War II, and Matt Damon starred in the failed project “The Great Wall” two years ago.

Spoils of war?

This American-Chinese honeymoon is being dampened by the trade war between the two countries, which has already brought about a dramatic drop in this year’s American films’ successes in China. A few months ago, in the midst of talks between the two sides regarding the future of trade, the Chinese offered a temptation in the form of willingness to open the movie market to more American films – in exchange for American concessions in other areas. Hollywood lobbyists, despised by Trump, are exerting pressure to include an industry benefit for any future agreement or at least to preserve the status quo.

The bottom line is that Hollywood now has efficient mechanisms for producing and marketing films that cost tens of billions of dollars a year, despite all of the at-home tech developments of TV, VCRs, and the internet. But ultimately, even the most successful marketing machine can not hawk a bad product over time and anyone looking for big success in this industry must, as in all industries, innovate. The cash cow that Hollywood has found overseas is an opportunity to do so – even if it means that we will be seeing lots of new faces.

The first weekend – peak development of opening weekend

| Date | Film | Weekend Revenue in

millions of dollars ($) |

| 2018 | The Avengers: Infinity War | 257 |

| 2015 | Star Wars: The Force Awakens | 247 |

| 2015 | Jurassic World | 208 |

| 2012 | The Avengers | 207 |

| 2011 | Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (Part 2) | 169 |

| 2008 | Dark Knight | 158 |

| 2007 | Spiderman 3 | 151 |

| 2006 | Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest | 135 |

| 2002 | Spiderman | 114 |

| 2001 | Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone | 90 |

| 1997 | The Lost World: Jurassic Park | 72 |

| 1995 | Batman Forever | 52 |

| 1993 | Jurassic Park | 47 |

* The article translated by Zoe Jordan